Celebrating Women in Translation Month

This month, we celebrate translated fiction by Women Authors: from epistolary fragments to auto fictional confession, from lyrical meditations to spare monologues, each book in this collection enacts its own quiet defiance: of genre, of expectation, of erasure.

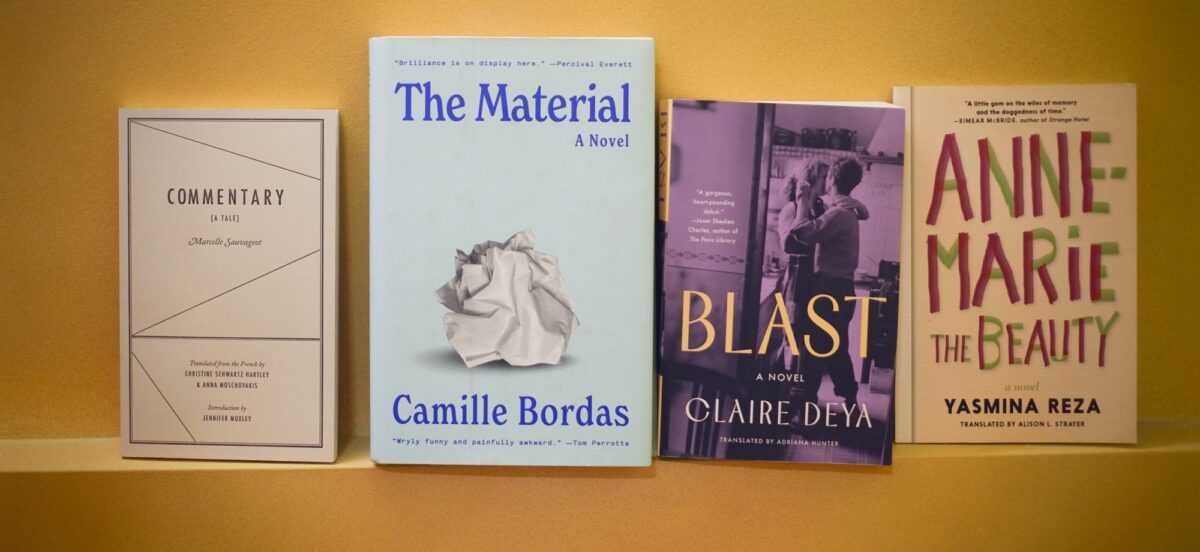

The first book in this list isn’t fiction in translation, but rather fiction written in translation. French-born Camille Bordas, like a few other literary shape-shifters, writes in English—her adopted literary tongue. The result, The Material, is a novel that reads with the precision of translation and the pulse of live performance: a deeply funny, self-aware meditation on the toll and thrill of turning life into art.

Commentary by Marcelle Sauvageot, a lost gem of early feminist modernism that refuses the pathos of romantic abandonment in favor of lucid, ferocious introspection. In The Pachinko Parlour, Elisa Shua Dusapin offers a taut and dreamlike portrait of diasporic identity and inherited silence, rendered in prose as precise as a scalpel. In Chicanes, Clara Schulmann composes a collective feminist chorus, pieced together from murmurs, outbursts, hesitations, and laughter—proving that how a woman speaks is often as radical as what she says.

With Anne-Marie the Beauty, Yasmina Reza gifts us a monologue of rueful, radiant aging—a one-woman show performed by a man, in a gesture of radical empathy that makes complaint itself a kind of art. And in Swimming in Paris, Colombe Schneck dives deep into the fluid terrain of memory, gender, and selfhood, emerging with something rare: a narrative at once bodily and philosophical, unadorned yet resonant.

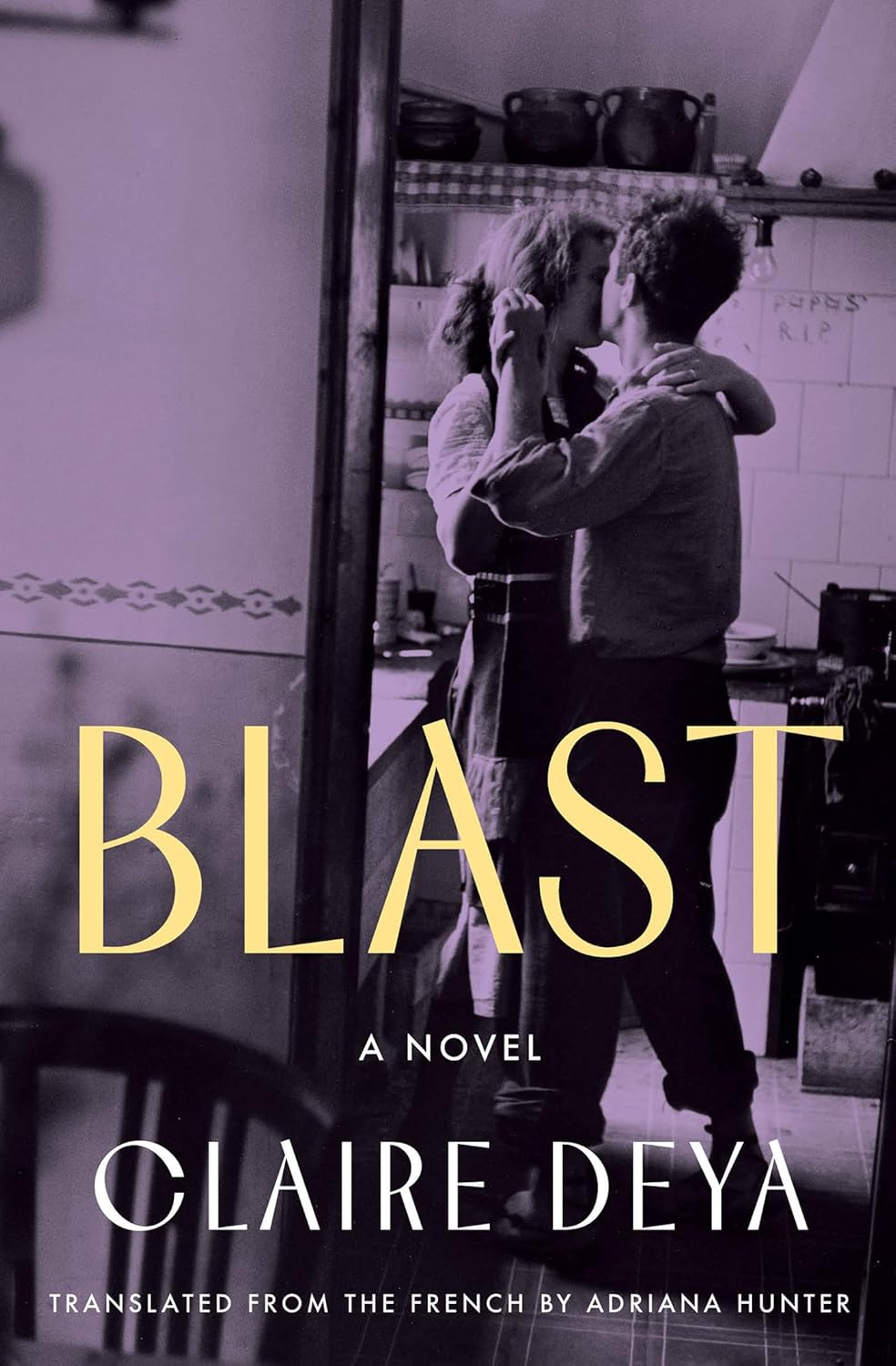

Finally, Claire Deya’s Blast revisits the false peace of postwar France, when the beaches were still mined and survival meant learning to walk beside your enemy. In taut, cinematic prose, Deya renders the unfinished violence of history with compassion and nerve.

These seven works offer more than literary excellence—they offer alternative cartographies of feeling, history, and form. They prove, if needed be, that fiction in translation is not a side genre or a niche concern, but a vital, animating force in literature.

Reading List

What if your every waking moment was up for grabs as punchline fodder? In The Material, Bordas hurls us into the neurotic, adrenaline-charged world of a university MFA program in stand-up comedy, where six students and four tutors spend eighteen relentless hours mining their lives—literally—for jokes. A failed apology letter? Comic gold. An active shooter lockdown? Potential setup. Even existential dread gets workshopped.

Bordas’s novel doesn’t just ask what makes something funny—it wonders what it costs to be funny on demand, all the time. From Artie, too handsome to be taken seriously, to Jo, a truther convinced Andy Kaufman is still alive, to tutors like Dorothy, who suspects her loneliness is her greatest stage asset, the cast is as sharply drawn as it is emotionally raw.

Snappy, skewering, and saturated with inner monologues dissecting every awkward glance and tragic impulse for “material,” this is a comedy about comedy—and the bleeding hearts behind the bit. Come for the laughs. Stay for the ache.

The Material by Camille Bordas (Viking)

Eighty years after her untimely death in a Davos sanatorium, Marcelle Sauvageot’s Commentary emerges in English for the first time—spare, incandescent, and utterly sui generis. This haunting and crystalline work, first published in 1933, hovers somewhere between an epistolary novel, a farewell letter, and a philosophical reckoning with love and loss. Written in the wake of a romantic betrayal and on the brink of the author’s death from tuberculosis, Commentary refuses easy sentimentality or moral consolation.

Instead, Sauvageot offers a ferocious anatomy of emotional clarity. Her narrator, dispatched to a remote cure, receives a parting letter from her lover—he is marrying another woman. What follows is not grief in the passive, romantic sense, but a lucid, razor-edged deconstruction of gender roles, bourgeois marriage, and the quiet indignities women are asked to bear. In a style as elegant as it is unflinching, Sauvageot strips love of its false veneers and insists on the dignity of choosing one’s own interior truth over conventional closure.

Though contemporaneous with Stefan Zweig’s more famously maudlin Letter from an Unknown Woman, Commentary is its antithesis. Where Zweig’s heroine dissolves in silence, Sauvageot’s narrator defiantly reclaims the right to interpret her own experience. This is love as creative force and radical self-possession; not a descent into death, but a flickering ascent toward freedom—etched with intellect, irony, and immense emotional control.

Published posthumously and out of print for decades, Commentary was long cherished by a devoted few, including Clara Malraux and René Crevel. Now restored in its original title and brought into English with grace, this slim volume is a revelation: a masterwork of modernist introspection and feminist resistance that refuses to be forgotten.

Commentary by Marcelle Sauvageot, Translated from the French, with an introduction by Lauren Elkin, Ugly Duckling Press

In her follow-up to Winter in Sokcho, Elisa Shua Dusapin once again delivers a slim, spellbinding novel of quiet rupture and emotional dislocation. Set in the sweltering heat of a Tokyo summer, The Pachinko Parlour follows Claire, a Korean-Swiss linguist adrift between generations and cultures. Her task—convincing her estranged Korean grandparents to return with her to their homeland for the first time since fleeing the civil war—becomes a slow reckoning with history, identity, and the silences that fracture families.

Dusapin writes with the precision of a poet and the atmospheric control of a filmmaker. The novel hums with tension beneath its stillness: jars of pickles float like embryos, conversations teeter on the brink of collapse, and the pachinko parlour itself—named “The Shiny”—becomes a site of fading illusions. Language, in all its fractured forms, is both barrier and bridge: Claire speaks to her grandparents in halting English, tutors a child in French, and studies Japanese while longing for a Korean fluency she’s never had.

What emerges is a delicate yet unflinching portrait of diasporic estrangement. Like the arcade machines that fill the parlour, Dusapin’s narrative is enigmatic, precise, and entrancingly repetitive—echoing motifs of fish, food, and drifting bodies to evoke Claire’s interior disquiet. Fans of Deborah Levy or Yoko Ogawa will recognize the craftsmanship at play here: elliptical, sensorial, and quietly devastating.

Though The Pachinko Parlour shares its emotional architecture with Winter in Sokcho, it deepens Dusapin’s exploration of inherited trauma and cultural displacement. A novel of elliptical beauty, this is storytelling at its most restrained and resonant—a luminous study of what it means to belong nowhere, and to carry history in one’s bones.

The Pachinko Parlour by Elisa Shua Dusapin, translated from the French by Aneesa Abbas Higgins, Open Letter

Click here to purchase this book with us

With biting wit and heartbreaking precision, Yasmina Reza’s Anne-Marie The Beauty delivers a monologue that is both elegy and celebration—of failure, of age, of life itself. In a brilliant stroke, Reza gives the role of Anne-Marie Mille—a forgotten actress, a woman both ordinary and indomitable—to a man: the extraordinary André Marcon. The result is less a gesture of provocation than of radical empathy.

The universal nature of complaint, as Anne-Marie herself calls it, knows no gender. As she recounts the disappointments of her stalled career, the humiliations of an aging body, and the loneliness that not even children can cure, Anne-Marie clings fiercely to her appetite for life. Her monologue is studded with mundane details—Ricola candies split in half for evening pleasure, an armoire hiding objects too depressing to bear—that provoke laughter as much as pathos.

This is Reza’s gift: turning despair into something deeply human, even joyful. Threaded through the performance is the Chaconne from Bach’s Partita No. 2, a piece whose melancholy theme blossoms into luminous variations. Reza’s text moves similarly—circling a minor key only to find, again and again, flashes of irrepressible light.

At once hilarious and heartrending, Anne-Marie the Beauty is a defiant homage to women who don’t go quietly, to the absurdity of aging, and to the quiet grace of enduring. It reminds us that even in the universal complaint, there is still joy—and always, beauty.

Anne-Marie The Beauty by Yasmina Reza, trans by Alison L. Strayer, Seven Stories Press

In Swimming in Paris, Colombe Schneck charts a life in three autofictional movements—Seventeen, Friendship, and Swimming—each a candid, unsparing meditation on the body, memory, and the illusions of freedom. Translated with grace by Lauren Elkin and Natasha Lehrer, the book is both a personal reckoning and a quiet homage to the feminist tradition of self-writing “à la Annie Ernaux”.

The collection begins with Seventeen, a lucid account of a teenage abortion—legal, safe, and, paradoxically, disempowering. Schneck’s body, given every freedom, still feels like a betrayal. In Friendship, memory slips into the third person, a distancing gesture as Schneck revisits illusions of youth, privilege, and permanence. In Swimming, the body reemerges—not as symbol or burden, but as lived experience. A breakup leads her to the pool, where she learns to breathe, to float, to become weightless. Swimming, here, becomes a metaphor for a new kind of freedom: not loud or triumphant, but rhythmic, elemental, self-contained. It’s a return to the body not as a site of shame or expectation, but of sensation and presence.

Schneck writes with precision, vulnerability, and rare directness. In a world still obsessed with performance—gendered, social, professional—Swimming in Paris offers the radical gesture of letting go. Of drifting, deliberately.

Swimming in Paris, by Colombe Schneck, trans by Natasha Lehrer and Lauren Elkin, Penguin Books

In the haunting days following World War II, peace proves more perilous than war. Claire Deya’s Blast opens in the spring of 1945 on the sun-soaked beaches of Hyères—booby-trapped by the Nazis, and now cleared by the very people they once sought to destroy. German POWs, members of the French Resistance, and civilian volunteers comb the sand for hidden mines with nothing but wooden sticks and trembling instinct, forced into fragile alliances that blur the lines between enemy and survivor.

A screenwriter and historian, Deya brings a cinematic sweep to this taut, intimate novel. Each character carries a secret: a plan to escape, a question of betrayal, a desperate search for love lost to the chaos of war. What binds them is the razor-thin margin between life and death—and the minefields that remain not just in the sand, but in the mind and heart.

Blast is a searing meditation on the unfinished business of war, where vengeance and grace, suspicion and tenderness, survival and surrender coexist in uneasy proximity. Deya asks: when the guns go quiet, what detonates next?

Blast by Claire Deya, trans by Adriana Hunter, Other Press