La Cache

“Living is moving from one space to another, going as far as possible to avoid getting hurt,” wrote Perec in Species of Spaces, and his sentence floats on our mind as we delve into Christophe Boltanski’s remarkable La Cache.

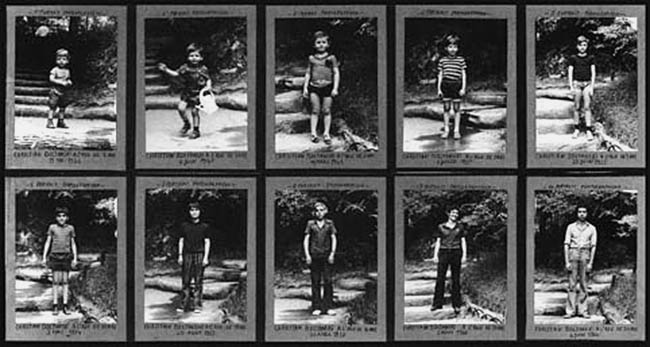

La Cache is a memoir of an exceptional family, among its members Christian Boltanski–one of France’s most important contemporary artists– and Luc Boltanski, director of research at the prestigious EHESS and the inventor of “pragmatic sociology.” Christophe, however, focuses his narratives on Luc and Christian’s parents, Etienne and Myriam Boltanski, and their unconventional lives as family heads, intellectuals, and leftists in a mansion on the luxurious rue de Grenelle. Christophe is Luc’s son, yet he spends his days at his grandparents’ before moving in with his immediate family on his fourteenth birthday.

“Their house was a palace, but they lived like tramps,” Christophe writes. “It would be a mistake to understand this mix of wandering, scarcity, dirt, and greed as the fads of some quirky grand bourgeois. Their weird behaviors were a rejection of good manners and social conventions all together. As a sign of rebellion against their bourgeois origins, their conducts created an inanity; an isolation from the world, and in this sense, they carry something pathological. The usual hierarchies were destroyed. Luxury was systematically bordering on paucity.”

The Boltanskis nourish themselves as if they’re one body: at the restaurant, they share a three-course meal between the four of them. Luc and Christian, the children, don’t go to school. They never celebrate birthdays and the passing of time is never referenced. They all travel together in a Fiat 500, a yogurt cup-shaped car with no doors or back windows. When vacationing, they sleep on top of each other in the car. This behavior finds its origins in Etienne and Myriam’s histories.

Born in 1896 to a Russian Jewish family, Etienne Boltanski is a pure product of the French Republic and a striking example of a successful integration. While his parents belonged to the poor working class, he was a brilliant medicine student, and ended up holding a prestigious position at the St. Antoine hospital. Grateful to the country that gave him a chance at a better life, Etienne converts to Catholicism, a decision that doesn’t help him in 1942, when he is forbidden to practice medicine and forced to wear a yellow star by the anti-Semitic laws of Petain’s France. Myriam was born into a poor catholic family and adopted by a rich heiress. While studying medicine, she developed polio and lost the use of her legs. Myriam is both the heart and the head of the family: her instincts will save her husband from deportation, but her lingering separation anxiety brings her children close to suffocation: Jean-Elie has never left the family apartment, and Christian Boltanski openly admits that without his brothers, he would have ended up in a psychiatric hospital.

At the heart of the book is a hole between the first and second floors of the Boltanski apartment. After a staged dispute with his wife, Etienne leaves the family residence with great fanfare, and comes back in the middle of the night to spend twenty months in this small, dark nest. This period of treachery and withdrawal informs the futures of the entire Boltanski family. Myriam keeps her children at arm’s length–often quite literally–and any attempt at emancipation is considered a deep betrayal. With humor and tenderness, Christophe Boltanski follows the joyful and traumatic travails of a one-of-a-kind family, both afraid and curious of everything.