Meet the Albertine Prize 2019 Nominated Authors

There’s still time to cast your vote for this year’s Albertine Prize, our reader’s choice award for French fiction in English translation

This year’s shortlist includes three women and two men who hail from France, Rwanda, Morocco, Mauritius, and Iran. The prize also serves to promote the efforts of the bold publishing houses that strive to bring these authors to American readers.

The nominated books map a literary journey that spans three continents and encompasses the outbreak of a civil war and the Rwandan genocide (Small Country, Gaël Faye); the epic journey of a family over three generations between Tehran and Paris and eastern and western cultures (Disoriental, Négar Djavadi); the creation and destruction of a family in a southwestern village in France (Waiting for Tomorrow, Nathacha Appanah), the ambivalent and tragic relationship between a family and a nanny (The Perfect Nanny, Leila Slimani), a narrative analysis of WWII outbreak and Nazi Germany’s annexation of Austria (The Order of the Day, Éric Vuillard).

__________________________________

Nathacha Appanah, Waiting for Tomorrow (tr. Geoffrey Strachan)

(Graywolf Press)

Adam, an immigrant from Mauritius, and Anita, who’s just moved to Paris from the countryside, meet at a party. They quickly fall in love, marry, and move to a village in southwestern France. Over time, the monotony of daily life begins to erode their marriage. But the arrival of Adèle, an undocumented immigrant from Mauritius who they hire to care for their daughter, sparks a short-lived burst of energy in both their personal and professional lives, before their story takes a tragic turn. Waiting for Tomorrow is a courageous examination of the artistic impulse, cultural identity, and family bonds.

Nathacha Appanah was born in Mauritius. Her award-winning novel The Last Brother, has been translated into sixteen languages. She lives and works in France as a journalist and translator.

*

What’s the best book you read this year?

I have just finished Milkman by Anna Burns and I think it’s a wonderful book. I just loved the way it challenged me—the language, the protagonists who bear no name, the tone and wit. Even if it is set some 40 years ago, I felt that it embraced brilliantly our time and its nagging anxieties. The novel had me at the very first sentence: “The day Somebody McSomebody put a gun to my breast and called me a cat and threatened to shoot me was the same day the milkman died.” Isn’t that just perfectly strange and beautiful?

What was the experience working with your translator?

I have been working with Geoffrey Strachan for some years now and feel very lucky. We have an old school way of working, if I may say so. Geoffrey will read my novel and write to me about his general impression and/or feeling, the difficulties he senses, the words or expressions he feels we should discuss. I write back (and by this I mean literally writing and posting the letter through this service called the Post Office—maybe with beautiful and strange stamps, because these things do still exist). He writes back and we agree on a phone meeting where we talk about the translation. Sometimes we have one or two letters again and some phone calls, if there are still some issues. He is very precise and thoughtful, and I am grateful to have him.

What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever received?

I have the feeling that I have had a lot of mansplaining bestowed upon me, whether I asked for it or not, since I first began to write. But maybe that’s not what this question is about. I think that the best writing advice I have found came from books or interviews of writers that I look up to. It may relate to the way they find a voice, a pace or, sometimes, just reading about how they tackle doubt and rejection is reassuring.

There is this sentence in Elisabeth Strout’s novel, My Name is Lucy Barton, that has kept me thinking. “We all have only one story [. . .] You’ll write your one story many ways. Don’t ever worry about story. You have only one.” I have been refuting that in my own writing and still, it seems there is much more to this. May be it’s that kind of advice that we would want, the ones that keep you thinking about why and how you write.

__________________________________

Négar Djavadi, Disoriental (tr. Tina Kover)

(Europa Editions)

In the waiting room of a Parisian fertility clinic, Kimiâ Sadr recalls her family history. As she sits alone amid couples, family narratives and personal recollections mix as her thoughts wander from her grandmother’s birth in a late 19th-century harem in northern Iran through her childhood in Tehran to her present incarnation as a 25-year-old French-Iranian punk fan. In this spirited, kaleidoscopic tale, key moments of Iranian history, politics, and culture punctuate stories of family drama and triumph.

Négar Djavadi was born in Iran in 1969 to a family of intellectuals opposed to the regimes of the Shah, then of Ayatollah Khomeini. She arrived in France at the age of eleven, having crossed the mountains of Kurdistan on horseback with her mother and sister. Djavadi is a screenwriter and lives in Paris.

*

At what time of day do you choose to write, and why?

I begin to write very early in the morning, around 5:30am. I’m not a heavy sleeper, so it doesn’t hurt me to wake up early and get immediately to work. Early in the day, I get the impression—given that around me all seems frozen in time—that nobody and nothing can disturb or interrupt me. I feel withdrawn into myself, serene, calm; absolutely free to write. Some mornings, when I don’t begin at this early hour, I find myself feeling as though my day has ceased even to be my own; as though, failing to begin the day properly, it has eluded me.

What books could you read and reread without ever wanting to stop ?

I often return to The Rebel by Albert Camus, in which Camus analyzes the history of rebellion, its causes, but also its transformation from a freedom-oriented movement into an oppressive one. Generally, though, I love to open any book by Virginia Woolf and read a few pages, savoring them as I would some kind of pastry, and yet at the same time listening intently to the rhythm of her prose, as one might listen to music.

The greatest lesson literature can teach us?

To write is to rewrite.

__________________________________

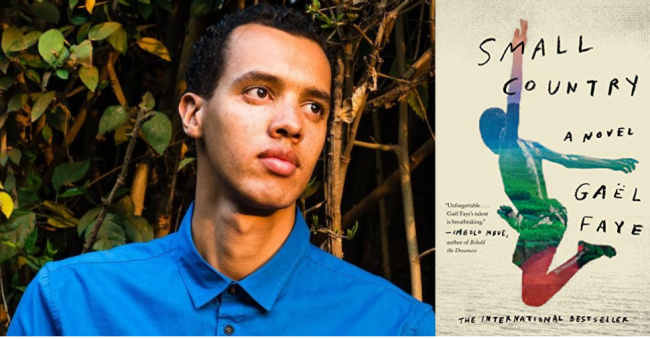

Gaël Faye, Small Country (tr. Sarah Ardizzone)

(Hogarth)

In 1992, ten-year-old Gabriel finds life in his Burundi neighborhood to be close to paradise. He and his friends enjoy days of laughter and adventure, but little do they know that their peaceful existence will be transformed when Burundi and Rwanda enter a tumultuous period of civil war and genocide. Beautifully written and heartfelt without ever being sentimental, Small Country is a magnificent debut novel that tells of a loss of innocence through the eyes of a child.

Gaël Faye is an author, songwriter, and hip-hop artist. He released his first solo album in 2013 and his first novel, Small Country, in 2016. Born in 1982 in Burundi to a French father and Rwandan mother, Faye moved to France with his family in 1995 after the outbreak of the civil war and the Rwandan genocide.

*

What’s the best book you’ve read this year?

Giovanni’s Room, by James Baldwin.

What time of day do you write?

I write in the morning, when my mind is at its sharpest, and late at night when it is hazier. This yields very different results, and allows me to find a point of balance between the two.

Which book(s) do you return to again and again?

Notebook of a Return to the Native Land by Aimé Césaire. I am trying to to learn it by heart, as its prose totally overwhelms me.

__________________________________

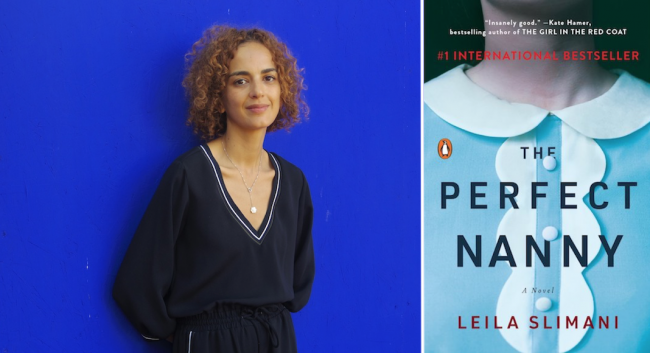

Leïla Slimani, The Perfect Nanny (tr. Sam Taylor)

(Penguin Press)

When Myriam, a French-Moroccan lawyer, decides to return to work after having children, she and her husband look for the perfect nanny. They never dreamed they would find Louise: a quiet, polite, devoted woman who sings, cleans, and stays late without complaint. But as the couple and the nanny become more co-dependent, jealousy and resentment mount. Building tension with every page, The Perfect Nanny is a riveting and bravely observed exploration of power, class, race, domesticity, and motherhood.

Leïla Slimani is a novelist and journalist. She was awarded France’s most prestigious literary prize, the Prix Goncourt, in 2016 for The Perfect Nanny. Her first novel, Adèle, was published in February 2019 in the US. Slimani’s latest work, an essay on sexuality in Morocco entitled Sexe et mensonges: la vie sexuelle au Maroc (Sex and lies: Sexuality in Morocco), has been nominated for non-fiction prizes in France.

*

Who do you most wish would read your book?

My father, but he died in 2004, ten years before I published my first book.

How do you tackle writer’s block?

In My Life as a Man, Philip Roth makes this very astute point: “Inspiration is for amateurs. For writers, writing is no more than work.” The lone remedy to the blank page is work, and dedication.

Which book(s) do you return to again and again?

The Unbearable Lightness of Being. It’s very strange, because I have the impression that I know it by heart and yet, at the same time, each new reading continues to overwhelm me, to awe me. I discover new sensation in it, I experience emotions until then unknown.

Which non-literary piece of culture—film, tv show, painting, song—could you not imagine your life without?

Films! I go to the movie theater nearly every day. As a child, I watched a lot of movies. My grandmother was a cinephile as was my father, who adored films from the golden age of Hollywood. Film has played an immense role in my passion for fiction, for characters.

__________________________________

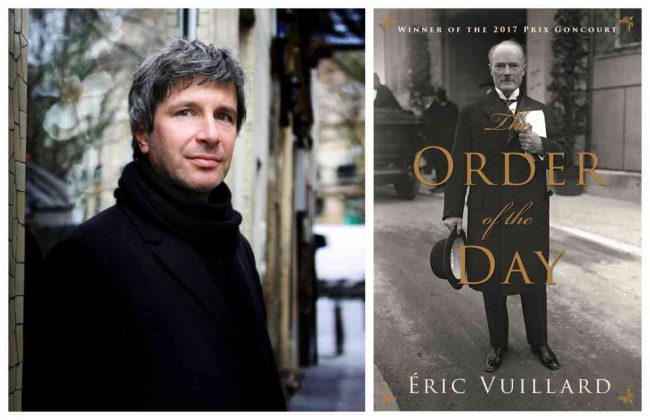

Éric Vuillard, The Order of the Day, (tr. Mark Polizzotti)

(Other Press)

Winner of the 2017 Prix Goncourt, this behind-the-scenes account of the manipulation, hubris, and greed that led to Nazi Germany’s annexation of Austria brilliantly dismantles the myth of an effortless victory and offers a dire warning for our current political crisis. In this vivid, compelling history, Éric Vuillard warns against the perils of willfully blind acquiescence and offers a crucial reminder that, ultimately, the worst is not inescapable.

Éric Vuillard is a writer and filmmaker. He has made two films and written seven books. He won the Prix Goncourt in 2017 for The Order of the Day.

*

What time of day do you write?

In the morning, I read and take notes outside, at a café. I return home to write whenever the desire to do so comes to me. The art of writing is at once an activity like any other, a job, and an activity profoundly and uniquely subordinate to desire.

Which book(s) do you return to again and again?

I don’t keep a book at my bedside. What interests and touches me is the great history of literature, this vibrant series of names: Stendhal, Hugo, Vallès, Malraux. Each of these names denotes a singular subjectivity; a body of work, but also an essential step forward for society. Stendhal makes us dream of Napoleon; Hugo of exile; Vallès of the Paris Commune; Zola of the Dreyfus Affair and miners’ strikes; Malraux of the Spanish Civil War. Of course, this principle also applies to Thoreau, Melville, Whitman, London, Baldwin. These names come to us through a double history, literary and social, and they haven’t finished returning to haunt us.

What’s the best writing advice you’ve ever received?

That, sometimes, when in the course of writing, a narrative will sink, and a book’s words will begin to ring untrue. Rather than distress myself when this happens, I pick up another book to work on. One writes leaning in the direction of an ever-elusive truth; this is why a new book will sometimes help me to understand what I failed to grasp in another. Another result is that, as time goes on, I have numerous books to work on at any given time.