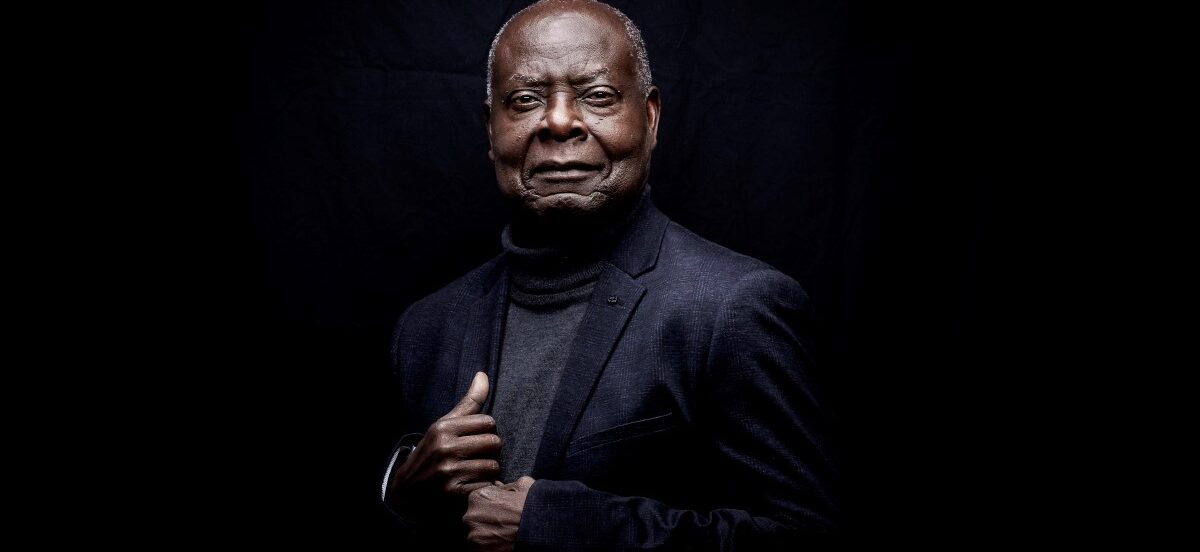

Emmanuel Dongala on 2021 Albertine Prize Finalist ‘The Bridgetower Sonata’

The life of Emmanuel Dongala is itself already a novel. Born in the Central African Republic, he pursued his scientific studies in Paris and New York in the 1960s, where he actively protested for civil rights and was also taken by a passion for jazz (as his exceptional collection of short stories Jazz and Palm Wine so clearly shows). A professor of chemistry in the Congo, he fled to the forest with his family when the war of independence began. There in the jungle, an emissary found him and gave him a visa for the United States which had been obtained thanks to the relentless efforts of none other than Philip Roth. He obtained a teaching post at Bard College and taught there for almost 30 years while, much to our luck, writing wonderful books.

Inspired by the music and complex history of the Congo, dictatorship, and the fate of women, his body of work is as powerful as it is varied, and includes Johnny Mad Dog, Jazz and Palm Wine, Little Boys Come from The Stars. We are grateful to Dongala for taking the time to answer our questions about his latest novel to date, The Bridgetower Sonata (tr by Marjolijn de Jager, Schaffner Press) a finalist for this year’s Albertine Prize.

Albertine Prize Committee: Why did you choose to write this book on Georges Bridgetower?

Emmanuel Dongala: A happy accident led me to write this book. While I was listening to a classical music program on the radio, the host announced that she was going to play Beethoven’s Kreutzer Sonata. After contextualizing the piece within the rest of Beethoven’s work, she added, as a minor detail, that the Sonata wasn’t originally written for Rodolphe Kreutzer but rather for a young Black violinist who has been completely forgotten today. This immediately piqued my curiosity. I did a little research to learn more, and as I went along, the subject became more and more fascinating. That’s how it became a book.

A.P.C.: This book is your first proper historical novel. What were the biggest difficulties you came across while writing it?

E.D.: It is true that Bridgetower’s travels and questioning of certain dominant ideas of the time evoke the picaresque novel, but I don’t claim any lineage to this. My novel isn’t “philosophical” in the sense of the 18th century. Rather it is situated in a dynamic of action, of claim and even of fight, to try to understand how freed Blacks, and especially their elite, were able to navigate through various issues to find their place in a changing Europe. For it is important to know that Europe in the late 18th and early 19th centuries was subject to extraordinary, even revolutionary, upheavals in art, science, and society; a period when the notion of European space began to emerge with the incessant displacement of musicians between various capitals, notably Paris, London, and Vienna.

A.P.C.: One of the striking features of your novel is the musicality of the text. Like your previous novels, the rhythm of your prose immediately plunges us into the heat of the action: we are with the characters in Paris, London, and Vienna, in streets, in salons. Do you work a lot by ear? Is sound an important component of your writing?

E.D.: Paradoxically, in this work whose very essence is music, I worked very little on the rhythm or the sound, unlike my previous books, notably my “oral” novel, Photo de groupe au bord du fleuve. In this one, I wanted to use a more classical writing style to adhere to the language of the time. My first concern was to return to the reality of the period as concretely as possible so that readers would feel as if they were taking part in conversations and debates in salons, so that they could admire the fashion of the time in all its detail, so that they could bath in the teeming atmosphere of certain neighborhoods in Paris and London with its “aigrefins,” its “vide-goussets” and so on. I wanted to make sure I avoided the ultimate trap, that of anachronism.

A.P.C.: In the novel, you describe the exciting life of the salons and especially the glass ceiling that hung over the elites of color during the Enlightenment and of which the Chevalier St. George would be the victim. Was this something you were aware of before writing the novel or did you realize it afterwards?

E.D.: As I mentioned above, I didn’t know a lot about this time period before writing the book and what I discovered afterwards, as I progressed in my research, was really a godsend for a novelist. I discovered that apart from the freed Blacks living in France and the majority of domestic servants brought back from the colonies by their masters or living on small trades, there was also an essentially mulatto elite that was very well integrated into society. They frequented salons, cultural sites, sporting events. This integration had its limits, however. For example, a cabal of artists barred the Chevalier of St. Georges from leading the Paris Opera because he was mulatto, despite his support from Queen Marie Antoinette whom he was very close to. Another striking example, even though it occurred in Vienna, was that of Angelo Soliman. Despite being very popular in the city, a Masonic brother of Haydn and Mozart whose Loge he directed, and a friend of King Frederick II of Prussia, he ended up stuffed and exhibited in a museum (?). Another juicy fact is that at the time, it was thought that there were too many Blacks in France and a special elite police called the “Black Police” was created to send those who were considered illegal back to the colonies.

The Bridgetower Sonata by Emmanuel Donagala, tr. by tr by Marjolijn de Jager, Schaffner Press, publisher in France by Actes Sud.

Click here to purchase this book with us.

The Albertine Prize, co-presented by Van Cleef & Arpels and the French Embassy, recognizes American readers’ favorite French-language fiction title that has been translated recently into English. Media partner: The New York Review of Books.